Malcolm Gladwell in his TED talk Choice, happiness and spaghetti sauce tells the story of Howard Moskowitz, a psychophysicist and market researcher and his insights into customer satisfaction. Howard’s big idea was that in many cases there was not one perfect platonic ideal for a particular product. Some people like chunky spaghetti sauce, some people like spicy, and some people like thin, blended spaghetti sauce. By trying to make a ‘one-size-fits-all’ product a lot of marketers and food scientists were making something that was the least offensive to most people, but was sub-optimal compared to multiple products in the same category, each tuned to the tastes of a particular ‘cluster’ of customers. Marketers call this horizontal segmentation. By acting on Howard’s advice companies were able to improve customer experiences by offering a range of products in the same category. If you’re looking down the aisle at your supermarket and are confronted with 20 different kinds of spaghetti sauce, cola or coffee from a single brand you probably have Howard to thank in part for that. By helping companies make products that meet customers needs Howard helped to make people happier, right?

More Choice != good

There is a problem with too much choice, however. In their landmark paper from 2000 psychologists Sheena Iyengar and Mark Lepper conducted an experiment with gourmet condiments. They set up a “tasting” stall inside a high-end grocery store. On one week-end they offered passers by a selection of 24 jams to try, and on the following week-end they offered only 6. Although slightly more shoppers stopped at the stall with lots of jams to try (60% vs only 40% for the stall with only a limited number to try) customers who were offered a large selection of jams only followed up their taste test with a purchase on 3% of cases. In contrast almost 30% of the customers at the limited-choice stall made a purchase. Since the “jam” paper in 2000 the picture has become even murkier. In some cases choice seems to have a positive effect, but in others the effect is definitely negative. Extra choices lead to decision fatigue which in turn can lead to impaired self-regulation and decision avoidance. For example research into voluntary retirement fund participation shows for every 10 options employees are presented with the level of participation in ANY fund goes down by 2%. As well as decision avoidance people also end up making flat-out worse decisions based on simplistic but irrelevant feature comparisons, because the complexity of truly important features multiplied by the number of options is too much to grapple with. In contrast some companies have reduced product lines in an effort to save money, with the expectation they’ll see a corresponding reduction in sales. However, when the reduction in product lines is carried out sales actually increase. While no-one wants to be faced with only one option there seems to be diminishing marginal utility in having lots of choices.

Not All Choices are Equal

It seems like the way in which the choice has to be made also greatly influences our happiness. In particular when choices need to be made quickly we tend to be happier with the outcome than when we have more time to deliberate. Even sadder still, we (humans) are terrible at forecasting our own feelings and believe incorrectly that having more time to deliberate will make us happier about our choices. Daniel Gilbert and Jane Ebert showed this in a 2002 paper where they created a photography course for Harvard students to participate in. After spending weeks taking a number of photos of the campus and developing them in the dark-room the students were asked to pick their two favourite photos, which were then blown up and printed as 8 x 10 glossy prints. The students were then told they could keep one of the prints, but were divided into 2 groups. One group had to choose immediately, the other group chose one but were given 4 days to change their minds. When surveyed later the students who had to decide immediately were much happier with their choice of photo. This throws some light on why maybe the hundreds of kinds of spaghetti sauce seems like a good idea to us - we don’t spend a lot of time deliberating over different kinds of spaghetti sauces, and we’re pretty terrible at predicting what is and isn’t going to make us happy.

So to summarise:

- Beyond a small number, more choices in a particular category has a number of negative consequences.

- We think we’ll be happier if we’re given more time to decide, but we are actually less happy.

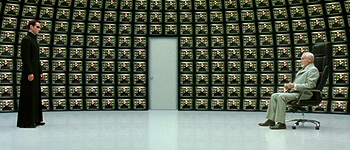

Is this ringing any alarm bells for developers, particularly front-end developers? We seem to have created the perfect storm for unhappiness by creating a plethora of things in every category in an environment where we have plenty of time to consider, deliberate and revise our decisions. As Neo so succinctly puts it in his conversation with the architect “the problem is choice”.

Image Credit: Renata F. Oliveria